None of the doctors ever told me my Dad was dying. Not the surgeon at Maine Med who first went in to do the biopsy of the lung. Not the surgeon at Mass General who did the biopsy of a lymph node. Not the oncologist at Maine Cancer Care the first few chemo treatments, which were also the only ones I could attend thanks to COVID. None of them.

But they didn’t have to. Mesothelioma is hard to Google, because the search results are heavily polluted by law firms in search of riches from ignorant or irresponsible manufacturers, but you can get the gist. And the gist is that it’s not good.

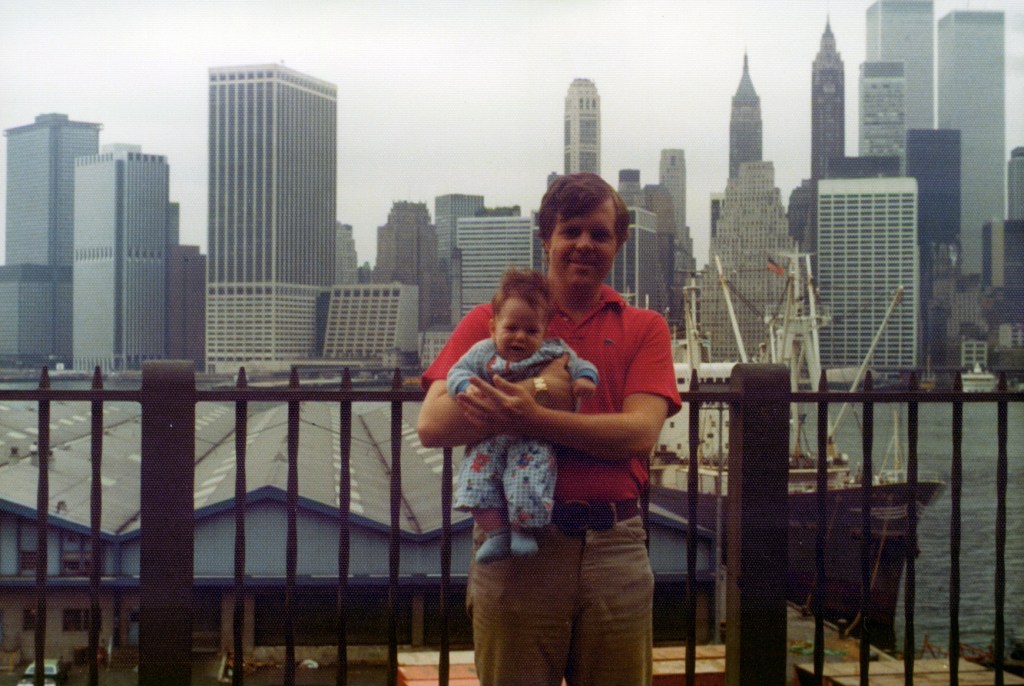

Mesothelioma is a malignant tumor that is caused by inhaling asbestos fibers. How my father, who spent his career on Wall Street theoretically well removed from the material that used to be common in building materials, firefighting gear and the like ended up with these fibers in his lung is an open question. We’ll never know for sure, but the evidence strongly suggests that it’s a consequence of my father going back to work downtown shortly after the 9/11 attacks. Per WikiPedia:

As New York City’s World Trade Center collapsed following the September 11 attacks, Lower Manhattan was blanketed in a mixture of building debris and combustible materials. This complex mixture gave rise to the concern that thousands of residents and workers in the area would be exposed to known hazards in the air and in the dust, such as asbestos, lead, glass fibers, and pulverized concrete. More than 1,000 tons of asbestos are thought to have been released into the air following the buildings’ destruction.

As an aside, before someone mentions the 9/11 victims fund, he was aware of it. Given the limited pool of funds, however, this was a non-starter for him because he would never have been willing to take money away from the first responders or their families.

Anyway, my father’s commute for four decades had him walk off the Path trains into the Trade Center en route to the Exchange every day. I know this because I did it with him one summer. He was fortunate enough to be on vacation up here in Maine not just for the attempted bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993 but for 9/11 as well. It would be as tragic as it would be ironic if he survived the attack in 2001 by not being there but the air he breathed when he returned to work ended up killing him twenty years later.

Pragmatist that he was, however, he’d have taken that trade.

It’s a similar trade, in fact, to the one he took when he was first diagnosed with cancer while at Harvard Business School in the early seventies. Cancer treatments were a little less sophisticated all those years ago, and to attack the cancer that he had the doctors irradiated large swaths of his body. Today, they can apparently target areas smaller than a dime. He was told that he had an 8% chance of dying within six weeks, and a 92% chance of living out most of the rest of a normal lifespan – albeit with some side effects.

Side effects that he accepted without complaint. His immune system went haywire, for one, and he developed allergies, the worst of which was poison ivy. If that so much as touched him, it was in his blood stream and off to the races. My childhood memories are always a little hazy, but I remember that. The side effects changed his hair color and density, and it left him permanently immuno-compromised. It’s weird when you’re a kid and your Dad’s mustache randomly grows in bright red.

Not that any of that mattered much: I don’t remember him missing a single day of work, ever.

For fifty years, the deal that he’d accepted was a good deal. Despite a few scares along the way, the cancer never came back until he noticed being short of breath and developed a chronic cough two years ago. Never one to visit a doctor unnecessarily, and probably for good reason given his history, he nevertheless went and ended up on the track that led to the diagnosis and the year that was 2020.

Christmas 2019 was a sad affair. My Dad had been diagnosed merely days before, and his weight loss left him gaunt and weary. When shown pictures of the dinner later, he replied with typical bleak humor, “shit, I look dead.” Still, we tried to take an optimistic tack with 2020. If there’s one thing I’ve learned about cancer today, it’s that your primary goal if they can’t cure you immediately is to buy time, because they might be able to in future.

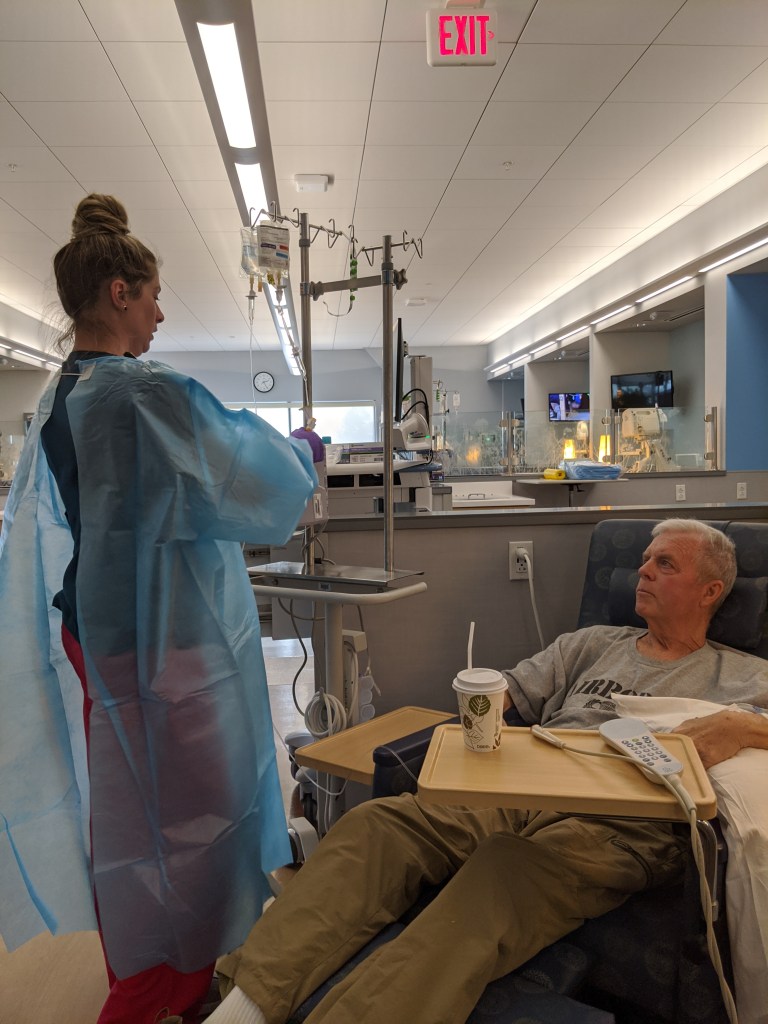

So that is what my Dad set out to do. Always goal oriented, his assessment was that based on trajectory at the time, he was unlikely to make it until the Fourth of July. Thus his goal was to make it beyond that date. To that end, he promised his oncologist one thing: that as long as they would agree to treat him, he would show up. At times, this meant employing some gamesmanship, no stranger to the lifelong athlete. As he continued to bleed weight he couldn’t afford to lose, he slyly wore heavier and heavier shoes to his weigh-in’s so they wouldn’t remove him from treatment.

So intent was he on continuing treatment, in fact, that he literally broke himself out of the hospital to get the toxic substance injected into his body. He’d fallen and shattered his femur – in retrospect, likely due to the fact that his heart had begun to stop unpredictably due either to a bad valve, arrhythmia’s or both.

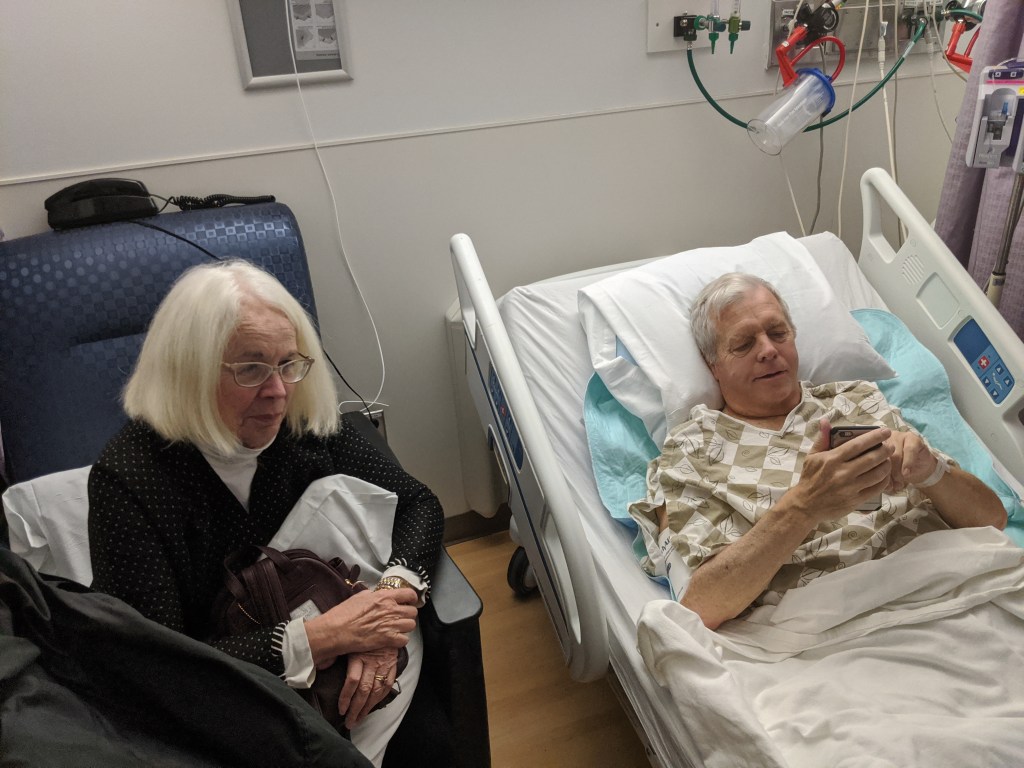

All in all in 2020, he dealt with the cancer, a bad valve in his heart, a congenital heart murmur gone rogue, five surgeries, and the broken leg. To add insult to injury, his access to the thing that made him most happy – his grandchildren, and to a lesser extent his children – was drawn down to a trickle thanks to the pandemic.

Insult, injury or otherwise, he fought to the last. Every time he seemed to take a hard won step forward, some new fresh hell would drop him back ten steps, or even twenty. But he was a fighter, and every time he got knocked down, he picked himself up off the mat and waded back in.

He died as a fighter, Monday morning. And despite the terminal prognosis, the cancer never won. His body may have ultimately failed him, but his spirit never did. It was his heart, or maybe his brain, that killed him. Not the cancer.

That terrible endurance was something I never wanted to learn from my Dad, but I did. He taught me many other things, some of which I wrote down in an admittedly lengthy letter to my then unborn daughter. Here are ten that I’ve thought about this week.

Have Priorities

My Dad grew up with very little. What wealth his family on one side had had at one point had largely petered out, and while his father always worked, you don’t become a minister for the money. Still, the family prioritized education, and so he went to Williams like his father and brother before him, and from there it was on to Harvard Business School. That provided him with access to jobs that featured, let’s just call it, high income potential. For the first time in his life, he had money. And but for his kids, that could have been his life.

Instead, he eventually came to a fork in the road. Down one path lay wealth and comfort; the other was precarious, stressful self-employment as an independent floor broker – the upside of which was predictable hours that allowed him to get home in time to coach my brother and I, first in soccer, later adding lacrosse in the spring.

Every family has different choices to make, and I can’t imagine the financial stress both of my parents bore. But I think I can speak for my brother when I say that I’m glad he chose us.

You Do What You Have To

When my Dad enlisted in the army, he and my mother were dirt poor and living in a trailer in Georgia. Every dollar, therefore, was precious. As a semi-related aside, if you get the chance, ask my Mom what it was like to work at a K-Mart in the deep south with a wicked Boston accent.

Anyway, after finding out that paratroopers got an extra pittance per month, my Dad signed up for jump school. The only problem with this transaction was that my Dad was terrified of heights. Every morning he had to jump, then, he’d get up and vomit because he was scared. But dollars were precious, so he got his wings.

Later, in business school, he had to go in regularly to get blasted with high doses of radiation. This had the intended effect of killing off the cancer and the unintended effect of giving him nearly full time nausea. He didn’t intend to miss class, however, so he merely requested a seat on the aisle so he could get to the bathroom quickly. All professors but one complied; the hold out required an appeal to the dean. He had no such impediments while competing in tennis tournaments during treatment, however; he’d merely vomit in between sets.

My Dad never really sat us down to talk about working through fear, sickness or injury. We just watched him.

Be Yourself

All the years my Dad worked on the various exchanges, he dressed – in general – as comfortably as the dress code permitted. He had nice suits and ties when they were needed, but his normal uniform was LL Bean chinos, a plain white shirt, his trading jacket and one of a couple of ties kept in his desk. That was who he was. My Dad paid no more attention to NYC fashion then he did to bars after work or coke in the bathrooms. His worst vice was coke, the soda.

It never occurred to me that this was in some way different or unique until I moved to New York City after college. Some friends had Armani suits and Gucci loafers. I was much more likely to be the one who kept us from getting into a bar because I was dressed like a 1930’s rail-riding hobo.

Like my Dad, for better or for worse, I knew who I was, and I never worried too much about what everyone else was up to.

Let Your Kids Be Who They Are

My Dad was an athlete all his life, and a very good one. Great, even. My brother and I grew up on stories of his freak athleticism, how he started on his college teams as a freshman, all of that. So naturally what I wanted more than anything else as a kid was to be like my Dad. But it was apparent pretty early that I was not going to be like my Dad.

I wasn’t a total loss on the field. I managed to start for teams in high school and college eventually, but particularly when I was a young kid and my height outpaced my coordination, I was a far cry from what my Dad might have reasonably expected of his progeny. Some, maybe most, former athlete Dads would have been embarassed by a kid like me. Others disappointed. Maybe both.

Whether I played well, and I usually didn’t as a kid, was not relevant to him. The only thing my Dad ever cared about was my effort. It could be five minutes of garbage time at the end of the game, and all my Dad asked was whether I had fun and tried my best.

I used to take that for granted. Looking back, I wonder if it was ever hard for him to watch me struggle. If it was, he never showed it.

Help Those Less Fortunate

He never used the word, as far as I’m aware, but my Dad had an innate understanding of his privilege, his humble socioeconomic origins notwithstanding. He came by it honestly, to be fair. As my Mom tells the story, their engagement party in Michigan was an interesting event because in the day’s prior my Dad’s father had been publicly excoriated for supporting women’s access to birth control and his mother had been arrested in Detroit after being part of a sit-in to protest an urban renewal effort that, no surprise, was slated to replace low income housing.

When he returned to Williams after his military service, he and my Mom ran the ABC House in Williamstown, which brought inner city kids out to a different life in the Berkshires. One of the kids that lived with them, Ted Ferriss, became a lifelong friend, and quarantined himself for two weeks to be able to visit my Dad in Maine from New York this fall.

He also believed in gender diversity within the workplace, and I can’t articulate that any better than the following snippet which was taken from an email I received from one of his former employees.

Your dad is one of the gruffest people I know but has the absolute best twinkle in his eye and biggest heart underneath the gruffness. I was living on my brother’s couch/floor for the first month in NYC and your dad continually was checking in on my apartment hunt and making sure I was doing ok in my transient state. No one else was doing that. I also loved what a big effort he made to hire women into a predominantly male industry and ensure we were all treated equally. Granted “equally” meant he treated us all like crap and made us haul waters from the main office blocks away down to the floor of the Amex, but to this day I’ll maintain that I was treated better at [REDACTED] than any other job I ever had in NYC. He made so many ridiculous jokes, but he always made sure we were in on the jokes instead of being the unaware butt of the joke. I always felt like part of the team / one of the guys / however you want to say it. It was just a great environment thanks to him, and a pretty unique situation for a 22 year old girl on a trading floor.

He used to talk to me about the importance of hiring people from different backgrounds when I was younger, and I didn’t fully appreciate its importance, or how unusual it was for an old white guy to appreciate it. I do now.

Principles Matter

My Dad was, first and foremost, a man of principle. He was rigidly, and at times, uncomfortably, honest. His moral code did not encompass shades of gray; for better and for worse, he was a man of black and white. There was right and there was wrong, and he never struggled much to tell one from another.

This was the moral compass that led him to enlist in the army. His number would probably have him drafted anyway, but his feeling was that if his country called him to serve, it was his duty to answer that call. Whether or not he approved of the Vietnam war was immaterial. He did not, he was simply of the opinion that it would not be appropriate for him to pick and choose when to serve.

This was also the moral compass that gave him a respect and appreciation for those who refused to serve. This is something he wrote almost a decade ago.

I recently heard from an old friend from grade school (in Switzerland). He attended Stanford and was in the ROTC program. Upon graduation, he turned down his commission as an Army Officer and refused to be drafted. He did not hide in Canada. Ultimately he was arrested and convicted as he should have been (later pardoned). He asked me if that was a problem for me. My answer was that he did what he believed in – very openly and suffered the consequences. I respect him for that.

In an era of fluid and ambiguous morals, my Dad was something of an anachronism. I don’t think I ever appreciated that enough.

You’re Not Better Than Anyone

My Dad was never a people person, exactly. My Mom, in fact, likes to say that my Dad was always better with children than adults, though arguably that’s more because he was so good with kids than deficient with adults. In any event, whatever his people skills, there is one thing my Dad positively excelled at, and that was extracting people’s life stories.

There’s a truism that everyone wants to talk about themselves. What my Dad wanted to talk about was the person he was talking to. Where were they from? Where did they go to school? What did they do for a living? How was business? You’d go to dinner and by the time the check came anyone at the table could have written a thousand page biography on the server.

This made for some very long dinners, and a lot of “Dad, you can’t ask that.” It also meant that my Dad stood out, and often connected with people in his life that no one had ever asked about.

I’ll never forget the time that I was attending a client analyst day held at the New York Stock Exchange. This being well after 9/11, security was high and thorough. After looking over my license, one of the guards looked up at me and said, “are you related to that Steve O’Grady?” After hearing that I was his son, he shouted down the line that I was “Steve O’Grady’s kid.” I got the most cursory of wand treatments, and they sent me on with “say hi to your Dad for us.”

My Dad came from nothing, and whatever he became in the world, he never forgot that.

Focus on What You Have

Growing up, I don’t remember any of my friends’ parents going through a stereotypical mid-life crisis, but that’s also not really the kind of thing a parent would discuss with their kids. What I do know is that my Dad didn’t spend much if any time focused on what he didn’t have. Part of that might have been that he didn’t have the time to worry about that between working full time and coaching the rest of it. But my Dad was also someone who focused on what was in front of him, not what anyone else had.

When he got sick, we talked about the prior bouts with cancer, and his view was that at a minimum, science had bought him fifty years. If they couldn’t give him another ten or five or two, well, at least he’d banked the fifty.

We also talked about his classmates at the Officer’s Candidate School, the ones whose names are etched into the black granite of the Vietnam Memorial. He got to live his life, they did not.

Whatever else he was, my Dad was not an ungrateful man.

How You Measure Your Life

Best known for his work on the business theory of disruption, Clayton Christensen’s most significant insight might have come in terms of how one thinks about their life. This was his advice:

Don’t worry about the level of individual prominence you have achieved; worry about the individuals you have helped become better people. This is my final recommendation: Think about the metric by which your life will be judged, and make a resolution to live every day so that in the end, your life will be judged a success.

If we accept this metric, my Dad’s life was a massively underappreciated success.

Since he died, work has trickled out widely in spite of our best efforts to inform those closest to him personally. Here is a random sampling of quotes I’ve gotten from people who knew my Dad. Kids he coached, grown ups he hired, all of whom got the full, sarcastic Steve O’Grady experience.

I’m very sorry to hear about your Dad. Wanted to send my condolences to you and your family. He left me with great memories coaching us when we were kids.

Your dad was a big influence on me and I recall many of the valuable lessons he imparted as our coach growing up. He will be missed.

I actually heard about his passing from a…colleague…a little earlier today. He started a chain with about 15 of us who were all hired by Steve around the same time and the consensus is clear, he impacted all of us in such a positive way and really helped us all get our foot in the door with our first “real jobs”. I’m sure this has been a really hard week, but I hope you can take a little bit of comfort in knowing your dad was loved and respected by so many of us, and will not be forgotten.

I was so sorry to hear about your dad. I have great memories of him and his time with and impact on all of us.

I have fond memories of spending time with your father in our younger years and also later in life as we became “adults”. He loved and supported your brother and you, your interests and of course your Mom. Obviously, your Dad sometimes gave us all tough love. It makes me smile and laugh to think back on his firm and sometimes joking delivery. He will be missed.

I’m sure when word gets out more publicly, there will be many, many more of these, because if there’s one thing I’ve realized, it’s that my Dad touched a great many lives. So many more than I ever realized.

My Dad was at heart a metrics person. I don’t think it ever occurred to him, however, to think about his life in terms to the raw number of lives he impacted. If he had, I think he would have been pleased at the numbers if eager to be dimissive of his actual impact.

Put One Foot in Front of the Other

COVID has made things more complicated for everyone, but I managed to keep most of the impact at arm’s distance until May 20th. After he got sick, my Dad felt it was important to remain as active as he could, and to keep busy. On that particular day, his job was to get gas for the ride on mower. Late that morning I got a frantic call from my Mom telling me that my Dad had fallen and shattered his leg.

What we didn’t know at that time was that his heart had begun to stop irregularly, and he wasn’t lucky in his timing. Toppling over in the parking lot of a gas station, he’d annihilated his femur. It was bad enough that he passed out and fallen without an ability to break his fall, but he’d lost so much of his athletic muscle mass due to the disease that there was nothing to cushion the blow.

The ambulance came, and my Mom couldn’t ride with him. He got to the hospital and none of us could go see him. He went under the knife with no one by his side, and trying to piece together his condition by phone after the fact when he was on painkillers with no one there to advocate for him was a literal nightmare.

Right before he went under, one of the nurses asked him if we was scared. His reply might be the best summary of his life I can think of. He told her, “What good would that do? You’re going to put me out. I’ll hope to wake up, and we’ll go from there.”

There was no waking up this time, not for any lack of fight on his part. Now my family has to go on from here.

I miss you, Dad. Wherever you are, I hope they have the Coke made from the Mexican sugar cane.

My father died unexpectedly on Christmas Eve, 2020 (just a few weeks ago) and I was very very moved by a note circulated throughout his neighborhood from a neighbor. The stories shared about your dad will comfort you forever. Thanks though for also sharing them with us, the whole world. Condolences on the loss of your dad (and all of our collective loss).

This is extraordinary Stephen. You were blessed have him as a dad and he to have you as a son. Yeah I cried reading.

Steve, your father sounds like an impressive fellow. I am sorry for your loss and sad that the world has lost someone who made people’s lives noticeably better in ways that mattered. That isn’t something most people can say.

I simply loved it. I worked with your dad on the amex for many years and he was a very stand up man. I lost my dad New Year’s Day 2021 so I also know your pain and can identify with the love u have. Ty for this.

Thank you for posting this. It’s always hard to lose a parent. It happens to all of us, but no is ever prepared.