I was taught from an early age that as bad as a given situation might be, things can always be worse. This was deeply engrained in me during my formative years, and that attitude is second nature in our family. On the occasions when we call each other with bad news, for example, the custom has always been to preface it with “well, the good news is that I don’t have cancer.”

On the one hand, this training has served me well over the years. It’s helped me maintain my perspective during periods that might otherwise have capsized me, and it’s been a reminder to appreciate what was still good in my life when things looked bleak. On the other, this is an approach that can obscure the fact that while things could be worse they, at times, could certainly be better.

Case in point was my health and fitness entering 2021. I’d successfully avoided COVID thanks to strict protocols and the privilege that allowed me to follow them. This was, inarguably, something to be appreciated: things could most certainly be worse. That enormous win aside, the trajectory of my health otherwise was headed south and picking up speed.

There were a lot of reasons for this. The pandemic took its toll on me, of course, as it did on everyone. The weight of living in isolation, holed up to protect ourselves from an invisible enemy that neither science nor our immune systems had ever seen before was bad. Adding to that load was suddenly losing half my workday to become a part time pre-K teacher as we pulled our daughter from school for 543 days. Spending that much more time with her was an incredible gift, of course, but came at the cost of pushing half my work hours into the evening, which in turn led to a serious case of revenge bedtime procrastination and very, very late nights as I’ll get to.

But it wasn’t just the pandemic, though that made everything else harder. Some of the other challenges were mundane in nature, merely physically taxing. We had to prepare our house to move in three weeks when it should have taken three months, for example, and I ended up having to do a lot of the literal heavy lifting on my own because Kate’s work blew up thanks to COVID and she ended up working 80 hour weeks. From trip after trip to storage units late into the night to blazing afternoons with a belt sander on our deck during the hottest month in Portland’s history, moving was at once the best thing we’ve done in a decade and yet deeply traumatic. And not just because of the torn rib cage muscle.

The month before COVID ignited here in the US, meanwhile, my Dad began chemotherapy to treat an aggressive case of mesothelioma. I was only able to go with him for the first few sessions; after that, he had to go alone because they admitted patients only – thanks, again, to COVID. When I visited him and my Mom between treatments, it was almost always at a distance – on their deck if it wasn’t too hot or cold, in their garage if it was. I was able to hug my father but a handful of times during his treatment, and less than a year later he was gone.

And of course all of the above played out against the backdrop of the worst President this country has ever seen tearing through guardrail after guardrail en route to damaging, perhaps permanently, the country that I love but had lamentably taken for granted. I never thought we’d see another Nixon; instead, impossibly, we got someone worse.

Recounting all of this may sound like I’m making excuses for where I was, but I’m not. Countless people, for instance, saw their newfound ability to work from home as an opportunity to get into better shape while I, instead, ended up in a flat spin. Handed an unfortunate combination of circumstances, my job was to adapt and take advantage. I failed.

But that failure, fortunately enough, did not have to be permanent. As the man once said, “it’s not how you start; it’s how you finish.”

If I was going to have a better finish, however, clearly something had to change. Several somethings, actually.

The issues facing me were numerous. My physical activity level had cratered, my sleep patterns were a mess, my diet had declined, I wasn’t drinking more on a daily basis but I was drinking more often, my blood pressure and resting heart rates were up and various more specific measures of cardio fitness like my VO2 max were miserable.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that after an extensive and almost completely unplanned reboot, I still have a long way to go but I’m slowly and steadily getting back on track. It took me sixty-one days, but I got back down to my pre-pandemic weight two weeks ago, which is a good start. My weight was up even before the pandemic started so I’ve got more yet to lose, but I continue to chip away. My blood pressure and resting heart rates are down, and the latter’s the best it’s been in a number of years. I’m getting more consistent sleep, and I’m down to drinks two to three days a week. As for my VO2 max, well, it still sucks but I’ve got an idea about that.

Just as it may have seemed like I was making excuses for the physical tailspin I’d found myself in, it seems possible that claims of pulling myself out of it – or, more accurately, starting to – might come across as a humblebrag. For whatever it’s worth, I assure you it’s nothing of the sort. All I’ve done so far is undo some of the damage of the last two years: there’s a lot more work to be done.

More to the point, a couple of weeks ago, one day after I set a personal record for my longest walk (we’ll get to that), my best friend ran 48 miles. At altitude. Losing weight I never should have gained in the first place, walking a few miles or getting my resting heart rate back to reasonable fitness levels is nothing to brag about.

The purpose of talking about all of this publicly – which isn’t particularly comfortable, is on the off chance that relating my own experience gives someone else who’s gotten off track some ideas, or maybe a nudge to course correct and get themselves headed back in the right direction. I’ve learned firsthand how inspiring other people’s experiences can be, as I’ll get to shortly.

Anyway, the logical question is what I’ve been doing differently. The answer is a number of things. One thing was clear early on: if I tried too hard to plan big things, it wasn’t going to work. Frankly if I’d thought about it much, I almost certainly would have fucked it up.

Instead I focused on baby steps, or an “incremental path to victory” as we might put it at work. The first of which was yoga, which is somewhat shocking given that even at my peak physical condition in high school or college I was about as flexible as a piece of cast iron.

Yoga

Per YouTube’s history, at 9:34 PM on January 17th, 2021, I searched for “yoga with adriene 30 days.” Looking back, that might be where things started. I certainly didn’t think of it in those terms, yoga was just something small that I could do. While my exposure to yoga was minimal and what experience I’d had suggested that I was bad at it, it made sense for two reasons. First, it was physical activity that seemed more accessible and sustainable than, say, online HIIT workouts. And second, I hoped it would pay dividends with improved flexibility, which has only become more of an issue as I’ve gotten older.

Both of those assumptions, as it turned out, have been born out. With maybe half a dozen exceptions, I’ve practiced yoga every day since that night. I’ve gone through every 30 day Yoga with Adriene program there is (one twice), a specialized gravity yoga course for tight hips and of late have focused on yoga for my back (see below). To be clear, I’m still absolutely terrible at yoga. But while I remain comically inflexible, I’ve made enough progress that I can now at least sit cross-legged on the floor or touch my toes. Accomplishments that my six year old daughter would laugh at, of course, and appropriately so, but basics I was just too stiff for for years.

But while yoga was a fantastic addition, I wanted to kill two birds with one stone and ramp back up to some cardio work while physically getting outside more. Enter walking.

Walking

My initial efforts at cardio focused on running. If you’ve only known me in recent years, this will come as a surprise, but I used to run a lot and reasonably well over longer distances. But over the years, I gradually fell out of the habit. To the point where it’s probably been three or four years since I’ve run a mile in less than ten minutes.

Trying to get back into the habit, I had three problems:

- Being out of shape, the added weight and lack of recent physical activity meant that I kept getting nagging injuries even when easing back in via the various “Couch-to-5K” programs. Nothing major, but just enough to be discouraging and stall my progress.

- Getting back into running was also frustrating psychologically. Intellectually I understood that between age and inactivity, I couldn’t just roll out of bed and perform as I used to. But part of me expected to, and that was irritating.

- Perhaps most importantly, however, I wanted physical activity to not to be my primary engine for weight loss but to contribute to it, and given the ramp time of the Couch-to-5K programs it’d be months, potentially, before I’d be running for long enough periods to see any material caloric impacts.

After tweaking my back during one of these running programs, then, and putting it on pause for fear of doing more serious damage, I decided that while I was healing I could at least get myself outside and rehab by walking a bit. I started just walking across the bridge to the island we live on and back to the house. It’s a little over a mile, so it was both quick (and beautiful).

Enjoying those walks, I gradually tacked on another half mile. Then another mile. Then two. But even as my distances increased I didn’t take walking seriously as part of a fitness routine until I met an older gentleman named Dean. I mentioned above that it’s surprising how someone relating their experiences can be inspiring, but that’s exactly what happened.

Everyone on the island knows Dean, both because he’s out walking every day and because he gives every car that passes a big, exaggerated wave and a smile. That and the fact that he clearly walked serious distances as you’d see him all over town was all I knew of the man.

Then he stopped me while I was out on one of my rehab walks.

When I first started walking, Dean and I would pass each other occasionally. He’d smile and wave, I’d nod and wave back and we’d go on about our business. After this happened a couple of times, however, he must have decided that I was becoming a regular and he slowed and stopped in front of me. He asked me where I was walking, how far, and pulled out his phone to give me suggestions for new trails to try. He talked about his own routes, and the difference walking had made in his own fitness. When we parted, now as acquainted fellow walkers, it felt almost like I’d been inducted into an exclusive, private club. More importantly for my purposes, however, I came away from that conversation with two important facts. First, that walking had helped him lose weight, and second that as someone who was probably two decades my senior, he was averaging 10.6 miles per day – and sometimes exceeded that significantly.

All of a sudden I stopped thinking of walking as merely something to resort to when I was unable to run. After that one brief conversation, which could not have come at a better time for me, walking was elevated to the status of legitimate exercise option. It was low impact enough that I could sustain it without injury (with the exception of an intermittently sore lower back due to my shitty posture), and it could contribute to weight loss provided one was willing to walk for distance. Which I was.

From Halloween on, then, I’ve been slowly increasing my mileage and I’m now averaging something like 40 miles a week, with one day off. I’m a far cry from Dean’s daily pace, admittedly, but to be fair he’s retired and the master of his schedule and I am neither.

Best case, I’ll get back to some running as my overall fitness improves. I know for a fact the ability is still in there because of the Olympic-level sprint I managed a couple of weeks back when I was out for a walk and saw a skunk lift its tail at me in what seemed like slow motion. But in the meantime this is something that I can do on a sustainable basis that is pleasant, gets me outside, delivers results and can even be incorporated into my workday if I have listen only calls, conference talks to catch up on or even just need to think through a piece I’m writing. I don’t have much hope, probably, of being the most famous Stephen in the state that enjoys walking, but I can live with that.

Few physical activities short of ultramarathons or the Iditarod are going to burn enough calories to drop weight if your diet is poor, however, which brings me to food.

Diet

Sadly, with one minor exception, I have no shocking diet tips or secrets to reveal. I’ve lost weight for the most part simply because I’m eating less. Many in the tech industry swear by keto or other nutrition hacking approaches, and more power to you if you’ve found something that works for you, but those have never held much appeal to me. The closest I come to these kinds of things is intermittent fasting, but that’s not deliberate on my part. To the extent that I practice something like that, it’s purely a function of the fact that we tend to eat dinner at six because we have a kindergartner and I haven’t eaten breakfast regularly since I was a kid.

The one minor exception I mentioned above is the Line Diet. I first encountered it via Rafe Colburn, but his site seems like it’s offline so here’s a piece from Jeremy Zawodny explaining the concept – though I never used the five day rolling average he mentions. Conceptually, it couldn’t be simpler: you enter a starting weight, a target weight and a target date. The spreadsheet (or iOS apps, search for line diet in the App Store) will then draw a line between those points and give you a weight you have to hit to stay on course. If you’re under your daily weight, you don’t need to do anything special. If you’ve over the weight, you eat light.

There’s no magic to it, but I’ve used this to successfully lose weight a couple of times in the past and it’s working well this time. It works, at least for me, because it’s an accountability mechanism. If you’re thinking about having a late night snack, for example, it forces you to consider what impact that might have on your weight tomorrow, and thus what you’ll be able to eat. It might not be the approach for everyone, but it’s what has worked for me in the past and what is working for me now. For whatever that’s worth.

One other thing I’ll mention is that I’m not rigid in my rules. Technically I don’t have “cheat days” in the way that some diets allow, but you’ll notice a pattern to the average amount of weight I lose – or don’t – per day of the week.

That’s not an accident. I’ve found that my approach is easier to sustain longer term if I allow myself the occasional indulgence on weekends. For me, as long as the overall trajectory is headed in the direction I need it to be I’m fine.

Last but not least, one thing to think about with weight loss is sleep.

Sleep

If you Google “poor sleep weight gain,” you’ll find dozens of pages of search results discussing the correlation been poor sleep and weight gain. Which intuitively makes sense; if you’re tired, your decision making suffers, your self-discipline is impaired and you may feel a need to make up for the sleep-induced lack of energy artificially via food or drink.

Basically what this meant for me was that I was fighting weight gain with one arm tied around my back, because my sleep habits were an absolute disaster.

I’ve always been a night owl, and if I needed any further proof of that there’s the fact that while some people’s kids are out cold at 6 there are nights where I’m pleading with mine to get the hell to sleep at 9:30. But being a night owl is one thing. Burning the candle at both ends, as I was, just isn’t sustainable or advisable.

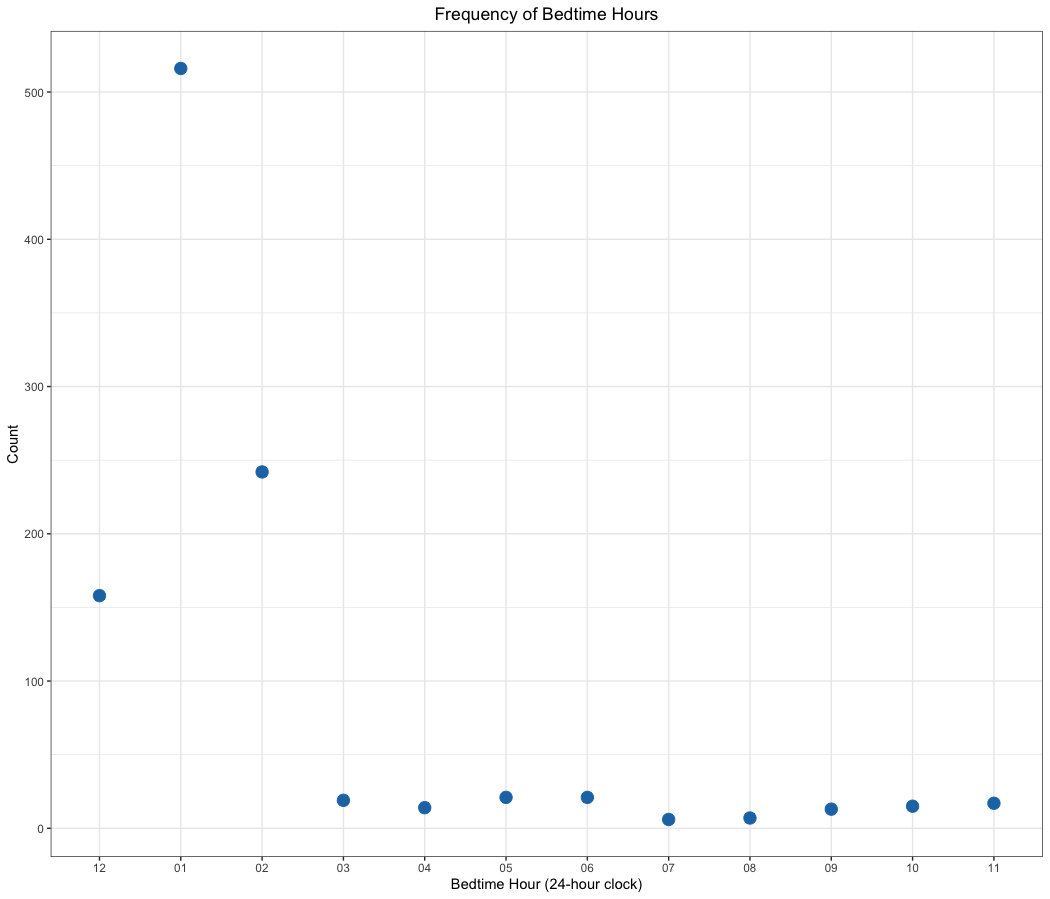

First, I was going to sleep too late. This is a chart of the hours at which I went to sleep since 2015 (with the exception of a couple of years for which I don’t have data). As an aside, I got the idea for these charts (and a bunch of the code) from the post here.

It’s fine to go to bed at 1 AM or 2 AM if you can sleep late the next day. But I have a six year old, and you generally don’t get to sleep late with six year olds – even six year olds that are night owls. So I wasn’t getting to sleep late.

While both of these charts are a bit misleading because they include the sleepless nights of a new parent and odd sleep patterns from the days when I was traveling, what the one above says plainly is that the majority of the time I don’t get even 400 minutes of sleep, which is a tick over six and a half hours.

Now I don’t need or frankly function well on a lot of sleep – seven hours is about the most I can handle without feeling paradoxically fatigued when I get up the next day. And I can technically function on five or even fewer hours, if necessary. But constantly getting less than six hours night after night was just not helping.

Now, instead of working nights or tinkering on pet projects (like the above charts) while absentmindedly having the 80’s movies I grew up on in the background, I’ve taken to heading to bed hours earlier and reading on my Kindle. As Craig Calcaterra describes below, I’d fallen out of the reading habit and am trying to be deliberate about getting back into it. It’s early days, but the results so far are promising.

Reading at night has the twin benefits of being a more worthwhile way to spend my time than checking Twitter for the hundred time that day or watching a movie for the fiftieth time and being an act that hastens rather than delays the onset of sleep as my laptop or phone would. More reading and more sleep are a virtuous rather than vicious cycle, and the additional sleep has a tangible impact on my overall health.

That’s it for the major changes, at least at this point. There are two other minor things to mention.

Other Things

- Apart from yoga, I’ve mostly neglected my strength training since I stopped going to my trainer at the beginning of the pandemic. Recently, however, I’ve begun to start back up there as well. As with the above, I haven’t done anything fancy – mostly just the tried and true pushups with some upper-body bodyweight work via our TRX. I’ll post back here when or if that expands.

- While a range of my health metrics from BP to heart rate have improved, my VO2 max has not as mentioned above. A big part of the issue is that my normal walking routes rarely spike my heart rate beyond 130 bpm or so, and that only for brief periods. To remedy this, I’m planning on introducing some basic jump rope work. I did a lot of rope work in high school and college as part of my training for other sports, and if done well it can get the heart rate up even if done only for brief periods. We’ll see what, if any, impact it has on my other cardio metrics, but it’s worth a shot.

The Net

If you’ve read this far, you either have too much time on your hands, we’re related or you’re looking for something. The best advice I can leave you with is this: if I can make these changes, you can too. Maybe not all at once, but the journey of a thousand steps and all that.

As Arthur Ashe put it, “Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can.”

Good luck.