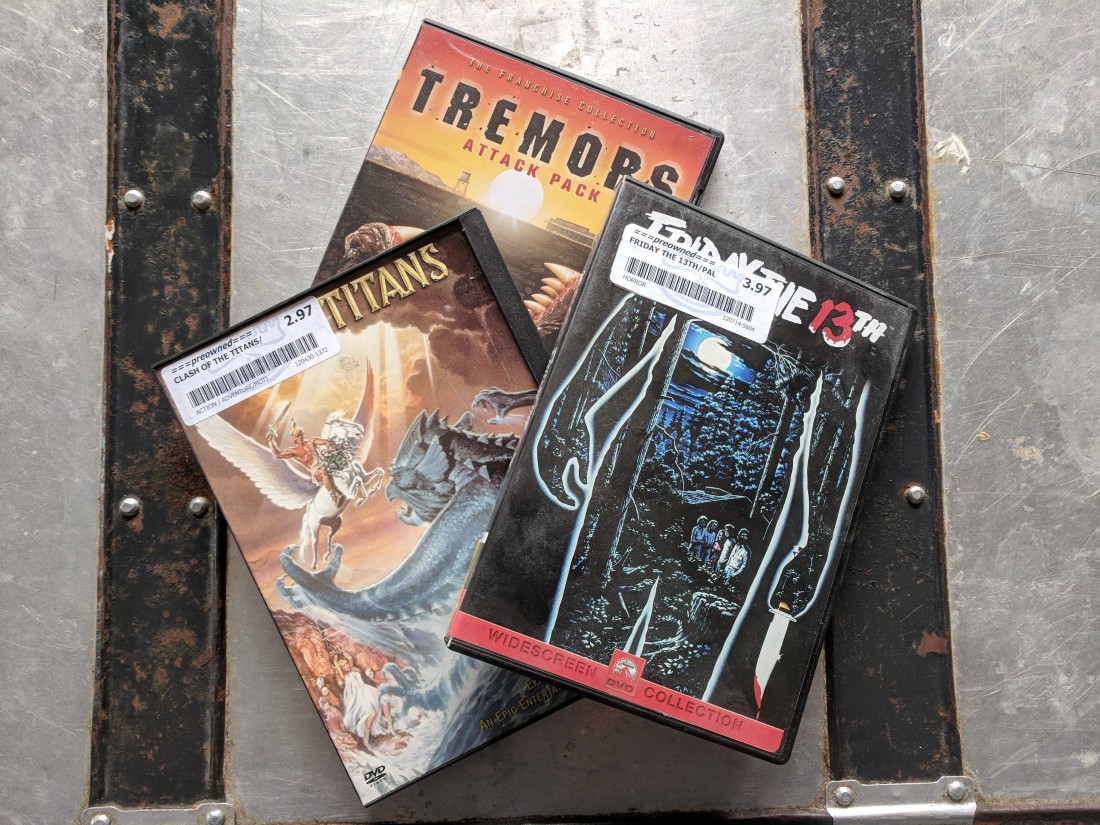

What I say old movies, what I mean are movies that I grew up with. Because I myself got old somehow, sometime. Some of these movies were out long before I was born, some were out a decade later. Some of them are good, most are not. If I’m really lucky, they’ve found refuge at the back end of Amazon or Netflix catalogs (hello again, Cloak & Dagger and Iron Eagle), but more often than not I have to track them down via used DVD stores (shoutout, Bull Moose).

People who know film will often tell you that movies and TV – TV especially – are in nearly every way fundamentally better products than they were when I was a kid. And while my tastes might betray the relevance of my opinion, this seems correct. Special effects have come a long way, but it’s more than that. Consider the quality of the child actors in movies like Super 8 or series like Stranger Things, for example. With all due respect to the nine year old Drew Barrymore of Firestarter and her contemporaries, the kids today are either better or better directed.

To be sure, not everything has changed – plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Movie tropes from my youth, for example – police procedurals, monster flicks, kids rule movies and on and on – are alive and well. But they are infinitely more self aware and better written than they were back in the days when we walked uphill to school both ways in the snow. As a rule, media today is simply more ambitious. In budget, clearly – the production locations for Game of Thrones being Exhibit A. But directors are thinking bigger. When It was filmed in 1990 as a TV miniseries, it was conceived of and delivered as a straight up horror genre entry. When it was turned into a feature film last year, the idea wasn’t to make a great horror movie, but a great movie, full stop.

All of which is an odd setup: if these old movies are objectively worse, why watch them? It’s not like there is or will be any shortage of new content available.

As it turns out, there are a number of reasons.

Some of it, of course, is raw, unfiltered nostalgia. The memories attached to some of these movies are so vivid that I can almost feel my little brother sitting next to me at the foot of our parents’ bed while we eat Swanson’s TV Dinners. No matter how bad some of these movies are, the narcotic effect of the memories they trigger is a far more compelling reward than technically excellent but more distant films of today.

My deep attachment to Jaws, for example, began the day my Dad let my friend Annie from across the street and I watch it on our Betamax set when we were *maybe* five (Annie’s Mom was not thrilled). On the other end of the spectrum, I’m not sure my little brother has ever really recovered from the time we watched Prom Night with our babysitter, Annie’s older brother.

One of those films is widely regarded as a magnificent accomplishment, the first and still best summer blockbuster. The other was considered a derivative, fortunately non-terminal career mistake for a young Jamie Lee Curtis. The memories these movies bring back, however, are not proportional to their critical regard.

There’s also the fact that in these multi-tasking, distracted days, the advantage of an old movie is that I’ve seen it before and therefore only need to devote a portion of my attention to it, much as you might put on classical music while you work.

And then there’s the novelty factor. You never know when someone essential to your childhood will show up in an early role. Why is Indy slumming it as a drag racer in American Graffiti? Is Kevin Bacon really going to be one of the red shirt camp counselors in Friday the 13th?

But the real reason I watch these things isn’t the cameos, the fact that I know some of them by heart or even the sepia trips down memory lane. What I’ve come to realize in watching the movies of my childhood is that all of them, quite unintentionally, are period pieces. Whether fresh or rotten on the Tomatometer, these movies are history. Mine, the cast and crews’, and the country’s.

They’re an answer to a fundamental question: what’s changed between now and then, and has it changed for the better?

- What the World Looked Like:

Like any worthy period piece, of course, there are the sets. Stranger Things had to expend incredible effort in making the present look like an approximation of the 1980’s. The films I grew up with just had to show up and roll camera. From old cars to old TVs to old commercials to old clothes to old hairstyles, there is something about watching movies of the past that’s like looking at pictures of yourself as a kid and wondering how in the hell you could have possibly thought Jams looked good. Cars that looked sleek and modern decades ago look quaint and impossibly antiquated. Unless they’re muscle cars like the Hemi Cuda from Phantasm, that is, in which case they look classic and bad ass. But there’s something about watching movies strewn with awful linoleum countertops, garish wallpaper and giant rotary phones that visually and viscerally reminds that you this was a different time, one that had its advantages. Hairstyles were weird, but kids could ride their bikes to school without getting their parents questioned by DHS. You didn’t have every song ever written available wirelessly, but people in general didn’t spend the bulk of their days looking down at a small electronic square, waiting for the next dopamine hit of an alert or inbound email. People smoked on airplanes, but you didn’t have to get virtually strip searched to get on one. It was a simpler time, and while that can be good as well as bad, it had its advantages. - What We Looked Like:

If you watch old movies, particularly the kids rule or slasher flicks, one of the things that stands out most is how normal the kids look. They don’t look like models and they don’t look like they’ve flown in from a Mr or Mrs Universe competition – they look like regular kids. In an era in which obesity levels are climbing and pervasive cameras and round the clock access have led to widespread body shaming issues, watching a bunch of normal teenagers is as refreshing as it is jarring. - What We Thought About Teenage Sex:

A great deal has been written on the moral messages of the early teen slasher flicks – Friday the 13th, Halloween and so on. As with the fixed set of rules that governed Wil E Coyote’s pursuit of the Road Runner, horror films of my generation were formulaic and followed patterns that transcended individual films or franchises. Teenage sex, for example, was punishable by death, while the most virtuous of the group inevitably ended up the lone survivor. So much of a cliché did these rules become, in fact, that the director of one of the series originally responsible for them, Nightmare on Elm Street‘s Wes Craven, went on to lampoon them in an updated nineties franchise called Scream. Joss Whedon did much the same with this decade’s Cabin in the Woods. If you watch It Follows, meanwhile, you’ll get an interesting sense of contrast between the sexual mores of the last century versus this one. - What We Accepted as Normal:

But it wasn’t just attitudes about teenage sex that have changed. When the main character in John Carpenter’s The Fog picks up a hitchhiking Jamie Lee Curtis while sipping on a Bud heavy, for example, neither the hitchhiking nor the casual drinking and driving were treated as particularly anomalous. Same with Teri Garr’s character fleeing her husband, played by Richard Dreyfuss, in Close Encounters of the Third Kind with three kids in a station wagon equipped with a grand total of zero car seats. Maybe the most startling is when Warren Beatty in The Parallax View is asked for his airfare – by the flight attendant after the plane has taken off. As Lou Reed said in 1973, “those were different times.” - What We Were Afraid Of:

Much as values have changed, so have the things that society fears. Growing up, people tended to be afraid of either the existential or the fantastical. The Damoclean threat of nuclear war in movies like Rocky IV, Wargames or even Spies Like Us at one of end of the spectrum, supernaturally evil killers like Fred Krueger or Jason Voorhees at the other. These days, we seem to worry less about nuclear war than we do about plagues, as in the case of movies like 28 Days Later, Contagion or [REC] (though admittedly Michael Crichton, as usual, was ahead of his time with The Andromeda Strain). On an individual level, meanwhile, we collectively seem to be more aware of the fact that we’re a lot more likely to be killed by other people than magical creatures. The cannibals of a Texas Chainsaw Massacre are frightening because they’re monsters, but the cannibals of Snowpiercer are arguably more so because, as Rod Serling once said, the monsters are us.Maybe the best evidence for how our fears have changed, however, is 1984’s Red Dawn. A movie about a Soviet-led invasion of the United States set in Colorado, it features a bunch of high school kids turned guerrillas with hunting rifles killing Cuban and Russian soldiers. It did this so well that the Gun Owners of America group honored the director for “dramatically depicting the importance in our time of the Second Amendment,” and the National Review Online places it 15 in its list of “The Best Conservative Movies.”

Today, however, with this President, many of those conservatives have very different attitudes about Russia. Attitudes which their parents would have found inexplicable and horrifying if not outright treasonous.

- What We Don’t Do Anymore:

In movies like The Monster Squad, a typical “kids rule” movie from the 1980’s, the homophobia sporadically on display isn’t the surprise: it’s how casual it is. While 2018 clearly cannot claim a perfect record when it comes to sexual preference or identification, it is heartening to watch movies from a few decades ago and think, “that would never be allowed in a movie today.” Baby steps, but progress nevertheless.Also, thanks in large part to Sigourney Weaver, there are many, many more women action stars these days. Angelina Jolie, Charlize Theron, Gal Gadot, Jennifer Lawrence, Kate Beckinsale, Linda Hamilton, Lucy Liu, Milla Jovovich, Scarlett Johansson, Uma Thurman, Zoe Saldana and all of the other women carrying action movies these days owe a debt to Ripley blowing the goddamn thing out of the airlock. Twice.

- What We Still Do:

As far as diversity goes, however, movies and TV are still generally awful. The good news is that Black Panther is, financially speaking, one of the most successful movies of all time. Get Out wasn’t quite the same money making juggernaut, but was similarly well received by critics. The bad news is the fact that these films remain the exception, exceptions which prove the rule. We’ve got a long way to go. As a believer, however, that economics are one of the most powerful change agents there is, it’s been absolutely delightful to see Black Panther approach the billion and a half revenue mark.